This article is part of the The Anatomy of a Technical Interview series.

The actual question is “What is a constructor, and what role does it play inside of an object?”.

Throughout my interview experience I have received a lot of answers to this question. Answers vary in shape and form, but are mostly along these lines: “It instantiates a class (or an object)” or “It sets the object’s properties”.

The problem with these “definitions” is that they are plain wrong. One worrying fact is that, for instance, in the first statement the interviewees use interchangeably the notions of class and object, which is a problem in itself.

Setting the object’s properties is somewhat true, technically speaking, but that’s not the point. Obviously an object’s properties are set whether or not there is a constructor defined (well, there is always an implicit parameterless constructor defined, even if there is no actual constructor declared in the class, but that’s a story for another day). So the properties are always initialized with their type’s default value.

What is an Object?

Well, in order to answer the original question, let’s setup a bit of a context. Let’s first see what an object is and what it does.

The primary responsibility of an object is to set boundaries around a state. The state of an object is represented by it’s properties and fields.

The object permits controlled access to this state through it’s public API. The API of an object is represented by all of it’s publicly accessible methods and properties.

An object’s job is to encapsulate state and expose a public API, that allows controlled manipulation of said state. The object is in control, and can either accept or reject requests to change that state.

The fact that an object controls the access and operation on its state represents a fundamental concept in OOP that is called encapsulation.

Contrary to popular belief encapsulation is not about hiding the state, or hiding information. It’s about controlling access.

An object can expose its internal state as read-only properties, and that’s okay.

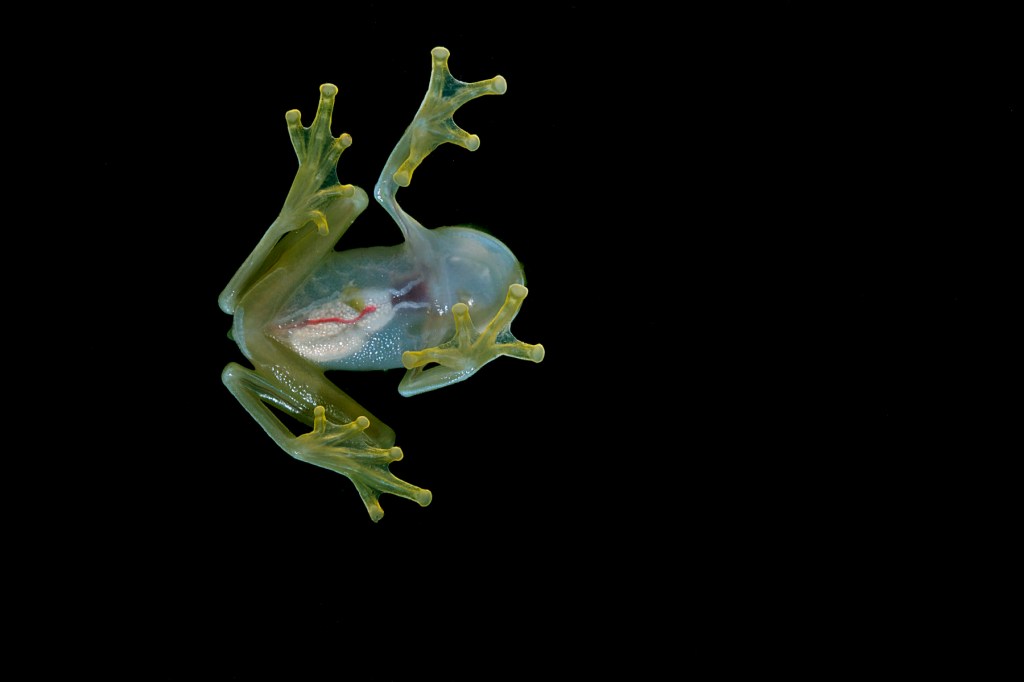

A very nice example from nature of an “object” that beautifully exemplifies encapsulation is an animal called the Glass Frog. This little critter has translucent skin on it’s tummy, therefore it’s heart, for instance, is visible. And just like a properly encapsulating object you can look, but you cannot touch. You can see the heart pumping, but you cannot interact with it directly.

By controlling access to its internal state through its public API, the object is able to represent and enforce business rules from the domain it is acting in. For example, there should be no way (except reflection, but that’s cheating) to be able to set a person’s name to null. And here null is just an example, but what I am really referring to is any value that is invalid within the given problem domain, be it null, empty string or whitespace.

In this context, the constructor, is a “special” method, the entry point, if you will, that allows us to set the object into an initial, valid state. It is very important to start from a known, valid state because this is the only way we can reason about our programs.